Welcome to "The Bishop Who Ate His Boots". This is a film I am making about my grandfather, Isaac Stringer. who was an adventurous missionary in the Arctic at the turn of the century. He later became Bishop of the Yukon and moved to Dawson City with my grandmother Sadie. In 1909, on one of his many walking tours over his vast diocese, he and a missionary worker, Charles Johnson, got lost in an early winter storm. They could not use their canoe as planned, so they had to walk 60 miles over a mountain range to get back to civilization. They ran out out of food and had to stew their spare moccasins to stay alive. Since then, Isaac Stringer became know as “The Bishop Who Ate His Boots"! My grandparents were very unique people living in controversial and adventurous times. The film shows my quest to learn as much as possible about them. There was much material with which to work. Isaac Stringer shot movies, took many still photos, and wrote detailed diaries.

My film is in the editing stages. This site will be updated with information as the project is completed.

This is a re-print from the Canadian Society of Cinematographers News Magazine March 2006:

|

|

|

Richard Stringer csc

The Bishop Who Ate His Boots: A Family Album

"A personal quest to find out more about my grandparents"

by Solange De Santis

"After years of filming documentaries on such subjects as native housing in the North and Canadian Finns in Russia during the 1930s, Richard Stringer csc has turned to his family history for his latest film.

The Bishop Who Ate His Boots is a work in progress and a labour of love, being the story of Stringer's grandfather, a well-known Anglican bishop named Isaac Stringer who worked in the western Arctic in the early years of the 20th century. Bishop Stringer kept an extensive diary and made 16mm films of the North, documenting a now-vanished way of life. Although a classic Christian missionary, he also adopted the ways of the native people and much of his low-pressure evangelizing took the form of what we today would call social work.

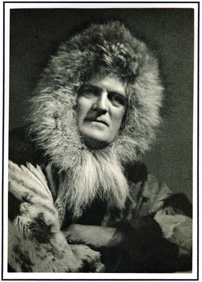

Isaac Stringer, The Bishop Who Ate His Boots

Isaac Stringer, The Bishop Who Ate His Boots

|

He and his wife, Sadie, lived for several years on one of the remotest places imaginable - Herschel Island, off the north coast of the Yukon in the Beaufort Sea. Sadie sturdily adapted to life in the North, giving birth to her first two children hundreds of miles from any medical aid, with only her husband for help.

It's been a similarly arduous journey for Toronto-based Richard Stringer, who has completed principal photography on the film, which he estimates will run about 50 minutes in a television version and 70 to 80 minutes in a DVD version.

"I started in 1990 with the idea of making the film," said Stringer, who was born in 1944 and never met his famous grandfather, who died in 1934. But he does have memories of his grandmother, who lived until 1955. Stringer's father, Wilfred (Isaac and Sadie had five children), died shortly after World War II. His mother, Clare, a British war bride, took young Richard to live in Winnipeg where he grew up.

Richard Stringer csc sets up his camera on a hill overlooking Whitehorse last October.

Richard Stringer csc sets up his camera on a hill overlooking Whitehorse last October.

|

Educated in Toronto at Ryerson University's film school, Stringer has had a long-established career, working on feature films, TV movies, TV episodes, commercials, corporate videos and documentaries. He won a Gemini Award in 2000 and CSC Awards in 2000 and 2003.

In February, 2004, he talked to author Pierre Berton, who was born and raised in the Yukon and knew the grandparental Stringers. "Berton said he (Isaac Stringer) took movies, 16mm black-and-white film in the 1920s and '30s, interesting documentaries of the North, great shots of people building igloos, making boots. From 1905 to 1930, my grandfather was bishop of the Yukon and he showed his films at the local church," said Stringer.

Isaac and Sadie Stringer with their two children - Herschel and Rowena - born without medical help on the Arctic Coast. Photo from the Anglican Church of Canada archives

Isaac and Sadie Stringer with their two children - Herschel and Rowena - born without medical help on the Arctic Coast. Photo from the Anglican Church of Canada archives

|

Berton, who was born in 1920, told Stringer that "it was a big thing - the bishop's films - we looked forward to that!"

In the spring of 2004, Stringer began to discuss his idea for a documentary with broadcasters at Toronto's Hot Docs film festival, but ran into competition from other Arctic programming. Nevertheless, he filmed an interview with Berton, who died in November that year, and in 2005 he received a $30,000 grant from the Ontario Arts Council. He began shooting more interviews and doing research at such institutions as the Anglican national church archives in Toronto and the Glenbow Museum in Calgary, which holds his grandfather's films.

'When that preacher came, just

like that, all the bad people stopped'

He realized that the film was more than just another documentary for him. "I will be on a personal quest to find out more about my grandparents," Stringer wrote in a grant proposal. "What made Isaac go up north? Was Isaac in conflict with the church's treatment of the natives or did he participate in unjust actions? Was he responsible for any residential school activity? What was my grandmother really like?"

What he found were two dedicated, resilient people. When Bishop Stringer arrived at Herschel Island in 1893, whaling ships were active in the Beaufort Sea, but the Europeans brought alcohol and disease to the native population along with trade goods. Bishop Stringer worked with the local Hudson's Bay Co. manager to stem the alcohol flow.

Now, on the Yukon Territory's web site (Herschel Island is now a territorial park), an Aklavik elder is quoted as saying, "You know that time when they first started to come, they had no priest . . . they started drinking, they try to kill each other, fought, drank. Their wives, they lost them to those white people. . . . When that preacher came, just like that, all the bad people stopped. Bishop Stringer, yeah!"

In February, 2004, Richard Stringer csc interviewed author Pierre Berton for Stringer's documentary on his grandfather, The Bishop Who Ate His Boots. Berton, born and raised in the Yukon, knew the grandparental Stringers and recalled that Isaac Stringer took 16mm black-and-white movies of the North in the 1920s and '30s and showed his films at the local church. "It was a big thing - the bishop's films - we looked forward to that!" said Berton, who died in November of 2004.

In February, 2004, Richard Stringer csc interviewed author Pierre Berton for Stringer's documentary on his grandfather, The Bishop Who Ate His Boots. Berton, born and raised in the Yukon, knew the grandparental Stringers and recalled that Isaac Stringer took 16mm black-and-white movies of the North in the 1920s and '30s and showed his films at the local church. "It was a big thing - the bishop's films - we looked forward to that!" said Berton, who died in November of 2004.

|

Sadie joined him in 1896. When her first child was born, she wrote in her diary, "My husband, who had some medical training, was my only attendant. I was tough and healthy and didn't worry and the little girl's birth seemed a happy omen."

Isaac learned some of the native languages and survival techniques. The latter served him well in 1909 when he and another missionary were lost in the wilderness for 30 days. They boiled up an extra pair of sealskin boots, giving them just enough animal nourishment to hang on until they reached a native camp. The story hit the newspapers and Pierre Berton said he believed it was the inspiration for Charlie Chaplin's boot-eating scene in the 1925 film, The Gold Rush.

In 1914, the Stringers travelled to England on a public relations and fundraising tour and King George V asked to meet them. In 1930, Bishop Stringer became the archbishop of Rupert's Land, the vast Anglican Church western region. Shortly thereafter, he discovered that nearly $1 million had been embezzled from education and church funds. The strain wore down his health and he died in 1934 at the age of 68.

Last fall, Richard Stringer travelled northwest to do research and film exteriors in the Yukon. He took the Sony XDCAM for interviews, but chose to shoot the territory's spectacular scenery on film, using Kodak's Vision2 50 daylight stock. "Film is better in that environment. You get a better capture, a better tonal range, with the extreme contrast of the white snow," he said. Kodak's new 50 daylight is an upgrade from an earlier version and the new film enables the cinematographer to "see into the shadows more."

Stringer has also been coping in the last year with a colon cancer diagnosis, but he said that despite chemotherapy treatment, he felt fairly good. "At this stage, I have no problem with energy," he said, but he added that some of the footage shows he lost some hair due to the chemo.

His investigative work left him feeling "pretty positive" about his grandfather, who did not appear to have much connection with the much-criticized residential school system, preferring to work toward the establishment of day schools for Inuit, white and Metis.

Now he wants to finish the film, scheduling editing for April, voiceovers for May and looking toward the Hot Docs festival next year. He was his own director and DOP, lugging equipment, scrounging for funding, persevering through adversity - a worthy descendent of his grandfather.

(For more on Canadian Finns in Russia during the 1930s, read Letters from Karelia, CSC News, April/2003 - www.csc.ca/news/archives.asp)"

Reprinted from the CSC News

|

|